Since 1990 the market for organic products has grown at a rapid pace, averaging 20-25 percent per year to reach $33 billion in 2005. This demand has driven a similar increase in organically managed farmland. Approximately 306,000 square kilometres (30.6 million hectares) worldwide are now farmed organically, representing approximately 2% of total world farmland. In addition, as of 2005 organic wild products are farmed on approximately 62 million hectares (IFOAM 2007:10).

Since 1990 the market for organic products has grown at a rapid pace, averaging 20-25 percent per year to reach $33 billion in 2005. This demand has driven a similar increase in organically managed farmland. Approximately 306,000 square kilometres (30.6 million hectares) worldwide are now farmed organically, representing approximately 2% of total world farmland. In addition, as of 2005 organic wild products are farmed on approximately 62 million hectares (IFOAM 2007:10).

Organic agricultural methods are internationally regulated and legally enforced by many nations, based in large part on the standards set by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM), an international umbrella organization for organic organizations established in 1972. IFOAM defines the overarching goal of organic farming as follows:

“Organic agriculture is a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and people. It relies on ecological processes,biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. Organic agriculture combines tradition, innovation and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and a good quality of life for all involved..”

Methods

“An organic farm, properly speaking, is not one that uses certain methods and substances and avoids others; it is a farm whose structure is formed in imitation of the structure of a natural system that has the integrity, the independence and the benign dependence of an organism” – Wendell Berry, “The Gift of Good Land”.

The term holistic is often used to describe organic farming. Enhancing soil health is the cornerstone of organic farming. A variety of methods are employed, including crop rotation, green manure, cover cropping, application of compost, and mulching. Organic farmers also use certain processed fertilizers such as seed meal, and various mineral powders such as rock phosphate and greensand, a naturally occurring form of potash. These methods help to control erosion, promote biodiversity, and enhance the health of the soil.

Pest control targets animal pests (including insects), fungi, weeds and disease. Organic pest control involves the cumulative effect of many techniques, including, allowing for an acceptable level of pest damage, encouraging or even introducing beneficial organisms, plant nutrition, careful crop selection and crop rotation, and physical/mechanical controls such as row covers and traps. These techniques generally provide benefits in addition to pest control – soil protection and improvement, fertilization, pollination, water conservation, season extension, etc. – and these benefits are both complementary and cumulative in overall effect on farm health . Effective organic pest control requires a thorough understanding of pest life cycles and interactions.

Weeds are controlled mechanically, thermically and through the use of covercrops and mulches.

History

The organic movement began in the 1930s and 1940s as a reaction to agriculture’s growing reliance on synthetic fertilizers. Artificial fertilizers had been created during the 18th century, initially with superphosphates and then ammonia derived fertilizers mass-produced using the Haber-Bosch process developed during World War I. These early fertilizers were cheap, powerful, and easy to transport in bulk. The 1940s has been referred to as the ‘pesticide era’. Sir Albert Howard is widely considered to be the father of organic farming.[8] Rudolf Steiner , an Austrian philosopher, made important strides in the earliest organic theory with his biodynamic agriculture. More work was done by J.I. Rodale in the United States, Lady Eve Balfour in the United Kingdom, and many others across the world.

As a percentage of total agricultural output, organic farming has remained tiny since its beginning. As environmental awareness and concern increased, the originally supply-driven movement became demand-driven. Standardized certification brought premium prices, and in some cases government subsidies attracted many farmers into converting. In the developing world, many farmers farm according to traditional methods but are not certified. In other cases, farmers in the developing world have converted out of necessity. As a proportion of total global agricultural output,organic output remains small, but it has been growing rapidly in many countries, notably in Europe.

Definitions and global market

Definitions:

Organic agriculture has been well defined in a number of documents, most notably by the International Federation of Organic AgricultureMovements – IFOAM: “Organic agriculture includes all agricultural systems that promote the environmentally, socially and economically sound production of food and fibers. These systems take local soil fertility as a key to successful production. By respecting the natural capacity of plants, animals and the landscape, it aims to optimise quality in all aspects of agriculture and the environment. Organic agriculture dramatically reduces external inputs by refraining from the use of chemo-synthetic fertilisers, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals. Instead it allows the powerful laws of nature to increase both agricultural yields and disease resistance. Organic agriculture adheres to globally accepted principles, which are implemented within local social-economic, climatic and cultural settings. As a logical consequence, IFOAM stresses and supports the development of self-supporting systems on local and regional levels” (Rungren, 2006).

Total area

In total there are more than 31 million hectares of certified organic agricultural land in the world. The countries with the largest areas of organicland are: Australia, China, Argentina, Italy, USA and Brazil. Some countries such as Liechtenstein, Austria, Switzerland and Italy have reached close to 10% of their agricultural land organic. Amongst African countries Tunisia and Uganda are having more than 1% of their agricultural land under certified organic production (Willer and Yussefi, 2006).

The organicmarket The organic market was valued at approximately US$ 27.8 billion in 2004 (Sahota, 2006) and has been growing at rates between 5 and 10% for at least a decade. The market share for certified organic products is between 0.5 and 4% in industrial countries with the highest market shares found in Denmark, Austria, Switzerland, Germany and Sweden. In overall terms the North American, German and British markets are the largest. The rapid and continued growth in organic markets in the developed world provides an impetus for farmers in both developed and developing countries to change agricultural practices to meet this demand (Willer and Yussefi, 2006).

In East Africa, the market for organic products is increasing as evidenced by emerging organic shops in the major cities, as people increasingly realise that “we are what we eat”, and often travel distances to buy healthy food particularly for babies and people suffering from various ailments caused by wrong nutrition. Even many conventional farmers using the current agrochemicals in their cash crops to sell to the cities and for export, have a kitchen garden for their families where no chemicals are used. As an added bonus organically produced products have often been found to have a much richer flavor (taste) as well as better nutritional content, and food connoisseurs over the world, including leading hotels and restaurants seek out organic food products solely for this reason.

The market share for organic food and clothing products is increasing world wide at a rate of about 25-30% yearly in most developed countries. In East Africa the market for organic products is increasing as evidenced by emerging organic shops are emerging in the major cities, as people increasingly realize that “we are what we eat”, and often travel distances to buy healthy food particularly for babies and people suffering from various ailments caused by wrong nutrition. Even many conventional farmers, using the current agrochemicals in their cash crops to sell to the cities and for export, have a kitchen garden for their families where no chemicals are used. As an added bonus organically produced products have often been found to have a much richer flavour (taste) as well as better nutritional content, and food connoisseurs over the world, including leading hotels and restaurants seek out organic food products solely for this reason.

Prices

The word “organic” put on a label of food is a major advertisement potentially resulting in higher market prices for products with this label. It is therefore also tempting to put such a label on non-organic food. For this reason ‘certification‘ of organically produced food is necessary as a consumer safeguard. Organically certified products can then be put a special label to tell the consumer that an independent accredited company has inspected and approved the production system as per standards set by accredited institutions.

Certification

The first institution to develop rules and regulations for organic farming and food production was the “Soil Association” of UK. From there many other institutions and international organisations such as IFOAM are now regulating the trade in organic products. Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda have developed their own individual standards for organic farming. A Kenya Government institution, Kenya Bureau of Standards (KBS) has been instrumental in this process in Kenya, and several institutions, primarily from Europe, now do the inspections for a fee to give producers the right to label their products “Certified Organic” and thereby obtain 30-50% higher market prices in ‘speciality markets.

The word “Organic” is now an international legal definition when applied to food and drink products.

To classify as “organic” all products in “developed” countries have to be certified by a Government approved body. For East Africa, export oforganic products has the implication that products must be certified by an approved overseas Government approved body, and so it is very expensive. The concept is still new in East Africa, but as consumer demand rises, it will also eventually become a requirement and the localcertification bodies must adapt and be approved by local Government bodies, or seek overseas accreditation in order to reduce certification costs to reasonable levels to allow local farmers find export markets for their products.

Organic production

Organic crop production

Organicfarming is a science – not a superstition! And some of the scientists in this connection are the traditional farmers themselves who through generations of observing what works, have come up with natural solutions with minimal external inputs to many farming problems. In East Africa, such experience has, for example, resulted in most small and medium scale farms using mixed cropping systems. Scientists are now realising that this practice is one of the best suited to tropical farm management.

Organic farming is based on the knowledge on how nature works and trying to work with nature rather than to keep fighting it. Scientists work to discover the laws of nature, and just as in physics there are such laws as gravity, there are also laws for how living organisms exist in harmony with each other and their surroundings. Likewise, the laws of ecology (=how healthy eco-systems work) need to be appreciated.

Organic meat / egg production

Consumer demand for organic meat in the UK and other “developed” countries has virtually exploded the last 10-15 years after many scares such as food and mouth disease, mad cow disease, chicken and fowl flu etc. The main stream consumer (not necessarily otherwise inclined towardsorganic food) has been looking for safe meat to eat and to feed his/her children. The demand of those countries for safe meat products is likely to increase many fold in the future. Also Kenya is experiencing a beginning in demand for “organic” livestock products. For example, “Kienyeji” eggs have long been fetching a much better price than conventionally produced eggs.

Soil is the constant factor in all farming operations, and livestock play an important role in the natural balance of the mixed organic farm. Organicfarmers the world over rely heavily on livestock manure to keep up the fertility of their farms. Good fodder plants such as legumes are also often soil fertility builders.

To produce organic meat (or milk, eggs), livestock must be fed organic fodder. In case of animals requiring a large amount of cereals such as chicken and milk producing animals, this requirement competes with people for food that may be in short supply. Only very good prices on the livestock products can encourage farmers to engage in such high cost value addition of their products. However “range fed” (purely grass fed) meat production is becoming more and more common, with consumers claiming superior taste quality, and possibly higher wellbeing after consuming these products.

The organic standards of different countries lay out rules for good organic management of livestock. This includes:

- Animal nutrition – livestock must be fed a minimum quantity of organic feed, and composition of this feed is also defined by the rules for each species and the environment in which it is grown.

- Animal behavioural welfare – minimum space requirements for each species is stipulated, as well as access to sunlight, shade and space for natural behavior patterns. Animal stress must be reduced to lowest possible level.

- Animal health – pests and diseases must be controlled as far as the vet is able. An animal should not be allowed to suffer unnecessarily where treatment is available. This means that livestock keeping is the only place in organic farming where agrochemicals are allowed, and only until alternative control measures are discovered. Where possible, less poisonous substances for tick and flea control are recommended, and on veterinary medicines – the conventional medicines are allowed where no natural cure is available or has been discovered.

- The manure collected beneath spray races can only be utilised as fertiliser on non-food plants (such as trees planted for firewood or timber etc).

- Conversion periods for animals not reared on the organic farm must be adhered to, so good record keeping is important.

- Good separation in butcheries is also a demand, so that chances of getting organic and non-organic meat mixed up is eliminated. If butchered in a conventional meat abattoir, the organic animals must be the first animals of the day to be slaughtered. If this is not possible for some reason, all machinery and equipment must be washed down thoroughly before an organic production can be started.

Organic milk production

One of the main constraints in any milk production is the disease Mastitis – or infection of the milk channels and udder. In East Africa, this disease is endemic in all milk producing areas. The cause is poor hygiene, and not as some pastoralists believe – “bad eyes, or witchcraft”. Mastitis causes milk producers to use enormous amounts of antibiotics in the milk production, and it is not certain that legal withdrawal time intervals for sending milk to market is always adhered to. Mastitis not only reduces production of milk but also taints the milk with “unclean” tastes or smells repulsive to consumers.

In production of “organic” milk all withdrawal times for antibiotics are doubled. Research is underway to find natural cures for this disease, but the most important ingredient in producing good quality milk whether conventional or organic is still: good hygiene. Recently a group of Danish organicfarmers got together to see if they could completely eliminate mastitis and the use of antibiotics from their herds using only good hygienic management practices and selection of milk cows showing higher resistance to this disease. Cows with frequent attacks of mastitis were slaughtered, and hygiene strictly supervised. The group has managed a long way to not only combat mastitis, but also reduce hygiene problems affecting keeping quality such as E. coli infection, to a level where consumers can safely drink the raw unpasteurised milk from these herds. The value addition done to milk this way is substantial.

For more information on organic farming, please check your local rules for organic certification or IFOAM certification standards.

See also the Kenya Bureau of Standards

Conversion to organic production

The rules of most certifying organisations (bodies) require a conversion period of at least one year, but sometimes two to three years. The reason is, sometimes several years must pass before residues of agrochemicals previously used finally disappear in the soil. During the conversionperiod, a farmer may have the disadvantage of not being allowed to use pesticides or chemical fertilisers. At the same, the farmer cannot yet sell the produce as organic. That could be a problem for the ‘convertees’ to organic production. Also after many years of using pesticides and chemical fertilisers, the farm may not have a good ecological balance. It may not yet have a healthy diversity of natural enemies of arthropod pests, beneficial soil micro-organisms, etc. For this reason, pests may cause problems, and it may be somewhat difficult to achieve a good level of balanced of bio-diversity. After a few years, however, both good pest management and soil fertility would be restored by a diverse healthy mixture of components of nature.

To help farmers earn money during the ‘difficult’ transition period of conversion, some certifying organisations allow farmers to label and sell their products as “organic in conversion” products. Customers who understand the systems may be willing to pay a bit higher price for the “organic inconversion” products than those produced through conventional farming.

Some advantages of converting to organicproduction

- The market for

organic products is growing

- Prices for organic products are generally higher than those derived from conventional farming, especially in ‘specialty’ markets in Europe. Also competition is somehow reduced compared to conventional products in both domestic and external markets

- Exposure to and intake of agrochemicals are drastically minimised

- Health of farming units is improved as organic agriculture focuses on nutrient cycles, soil health and a balanced diverse ecosystem

Some disadvantages of converting to organicproduction

- Yields may be somewhat lower, mostly because of the difficulties of providing enough organic fertilisers. But in general, this will depend upon the system previously employed by the farmer. Farm systems that intensively use agrochemicals can expect a decrease in yields, often estimated at between 5 and 20%. This occurs mostly in the initial years of conversion – as the soil recovers its natural fertility and farmers learn new management techniques. By contrast the transition from traditional agriculture in rain-fed areas to organic farming very frequently leads to increased yields

- Pests may be difficult to initially manage during early stages of transition period to organic production compared to conventional farming whereby there is an array of synthetic pesticides available and avoidable in the local market. But most certifying organisations do allow some low-toxicity tools such as biological pesticides (e.g. virus based products against caterpillars, Bt products also against caterpillars, compost ‘teas’ against diseases)

Some rules that farmers converting to organicproduction must follow and prescribed by many certifying organisations include:

- No synthetic pesticides, chemical fertilisers or growth regulators should be used within the past few years to conversion. This is because some agrochemicals can persist in the soil for several years, contaminating crops that are supposed to be chemical-free

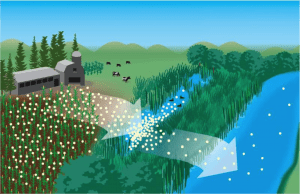

- To avoid the risk that pesticide sprays drift carried by the wind from neighbouring not organic farms onto the organic farms, the organic farms should have a (living) fence and a border of around 10 metres (Foodlink Standard). The organic farms should also take measures that the neighbouring not organic farms do not contaminate the organic farms with pesticides or chemical fertilisers through run-off water, etc

- Many certifying organisations allow the use of biological pesticides (such as viruses and Bt for control of caterpillars) and also allow the use of some inorganic fertilisers (such as rock phosphate or lime)

- Organic farmers must have a long-term plan for maintaining the fertility of the soil (e.g. green manure, farmyard manure, mulches, etc). Many certifying organisations want the entire organic farm to be managed in a way that will protect and improve the soil over a long-term, and recycle nutrients as much as possible

Organic certification

Organic farming is distinguished by formal standards regulating production methods, and in some cases, final output. Standards may be voluntary or legislated. As early as the 1970s, private associations created standards, against which organic producers could voluntarily have themselves certified. In the 1980s, governments began to produce organic production guidelines. Beginning in the 1990s, a trend toward legislation of standards began, most notably the EU-Eco-regulation developed in the European Union. As of 2007 over 60 countries have regulations on organicfarming (IFOAM 2007:11).

Organic Agriculture also is the only government enforced humane laws, such as limited to de-beaking on chickens, guarantee to pasture time to cows, and more humane ways to deal with bees[citation needed].

In 1991, the European Commission formulated the first government system to regulate organic labeling, setting the rules for 12 countries. Organiccertification became mandatory and was also required for organic imports. The mandatory certification solidified consumer trust in organicproducts.

The international framework for organic farming is provided by IFOAM. For IFOAM members, organic agriculture is based upon the Principles ofOrganic Agriculture and the IFOAM Norms. The IFOAM Norms consist of the IFOAM Basic Standards and IFOAM Accreditation Criteria.

The IFOAM Basic Standards are a set of “standards for standards.” They are established through a democratic and international process and reflect the current state of the art for organic production and processing. They are best seen as a work in progress to lead the continued development of organic practices worldwide. They provide a framework for national and regional standard-setting and certification bodies to develop detailed certification standards that are responsive to local conditions.

Legislated standards are established at the national level, and vary from country to country. In recent years, many countries have legislatedorganic production, including the EU nations (1990s), Japan (2001), and the US (2002). Non-governmental national and international associations also have their own production standards. In countries where production is regulated, these agencies must be accredited by the government.

- Information Source Links

- Garrity, D., Okono, A., Grayson, M. and Parrott, S. (eds) (2006). World Agroforestry into the Future. World Agroforestry Centre.

- Gunner, Rundgren (2006). Organic Agriculture and Food Security. IFOAM Dossier Organic Agriculture & Food Security. ISBN: 3-934055-66-4

- Kenya Bureau of Standards: www.kebs.org/

- Njoroge, J.W. and Manu, C. (Eds)(1999). Organic Farming. A textbook for Post-Secondary Education. Published by Kenya Institute ofOrganic Farming (KIOF). ISBN 9966-9977-1-7.

- Oestergaard, Troels V. (Ed.) (1991). Oekelogisk Landbrug – en Haandbog (Organic farming – a handbook) . G.E.C Gads forlag, Denmark 1991.

- Sahota, A. (2006). Overview of the Global Market for Organic Food and Drink. In Willer & Yussefi (2006)

- Schroth, G. and Sinclair, F.L. (eds) (2003). Trees, Crops and Soil Fertility, Concepts and Research Methods. CAB International 2003.

- Willer, H. and Yussefi, M. (eds) (2006). The World of Organic Agriculture: Statistics and Emerging Trends. IFOAM, Bonn

- Wright, Simon; McCrea, Diane (Eds) (2000). Handbook of Organic Food Processing & Production, Second edition, Chapman Hall UK.