The quality of turf depends on color, density, and absence of insects and disease. Color has long been overrated as a standard for a quality lawn. In many cases, a normal high-quality color should not be dark green. This is the case with centipedegrass and carpetgrass, both of which are naturally yellow-green. Over fertilizing to get dark green color generally leads to problems. Sod density and absence of insects and diseases are just as important as turf color.

The quality of turf depends on color, density, and absence of insects and disease. Color has long been overrated as a standard for a quality lawn. In many cases, a normal high-quality color should not be dark green. This is the case with centipedegrass and carpetgrass, both of which are naturally yellow-green. Over fertilizing to get dark green color generally leads to problems. Sod density and absence of insects and diseases are just as important as turf color.

Certain maintenance requirements are necessary for quality lawns. Basic chores for having a quality lawn include proper fertilizing, watering, mowing, and controlling weeds, diseases, and pests.

Fertilization

Turfgrasses must be properly fertilized to stay the right color, thickness, and health. Also, a well-fed grass recovers more quickly from stress and is more aggressive against weeds. As with all living things, proper nutrition is important to prevent diseases and insects. The lawn grasses discussed in this publication have different fertilization requirements, depending on the type of soils you have and the climate zone where you live.

Fertilization programs.

A fertilization program begins with soil testing, which tells the status of nutrients in your soil. Recommendations then can be made specifically for your lawn. If you have taken soil samples before planting, refer to the report for the recommendation needed to correct your soil problems.

If you have not taken soil samples, ask your county Extension agent for soil sampling boxes and an instruction sheet. Send soil samples to the Soil Testing Laboratory at Mississippi State University for analysis. There is a small fee. Be sure to indicate what kind of grass you will be using for your lawn.

Fertilizer and lime recommendations will be made for your own grass and soil needs. Results and recommendations will be returned directly to you from the Soil Testing Lab. If you have any questions about the report, feel free to contact your Extension agent.

Once you have corrected the early soil nutrition problems according to the recommendations from the Soil Testing Lab, you can follow the suggested fertilization programs shown in this publication. These programs suggest certain nutrients and when to apply them.

Soil testing should then become routine for managing the home lawn. A sample taken once every 3 years is ideal. This periodic sampling is necessary because of the changing conditions of soil chemistry.

Liming.

When soil tests indicate the need for lime, be sure to follow the recommendations carefully. Two common sources of lime are calcitic lime (ground agricultural lime) and dolomitic lime (dolomite). You can apply lime any time in the year, but you should apply no more than 50 pounds per 1,000 square feet to actively growing turf.

Several applications may be necessary to apply the total amount recommended by the soil test report. For example, if the soil test report recommends 100 pounds of lime per 1,000 square feet, you should split the amount into two applications, each using 50 pounds per 1,000 square feet.

Soil acidity varies according to soil type. A soil test shows the soil acidity level, commonly referred to as “soil pH.” The degree of soil acidity is indicated by pH numbers ranging from 1 to 14.

Maintaining a proper pH for your lawn grass is important, because soil pH determines how the soil nutrients are used. Fertilizers work much better when you keep the proper pH.

Nutrients Are Needed

The major nutrients needed for quality lawns are nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and iron. All are needed for quality turf, but some are more important than others. Grasses use nitrogen more than any other nutrient. Bermudagrass and zoysiagrass require large amounts of nitrogen during the growing season. Others, including centipedegrass, carpetgrass, and creeping red fescue, require only small amounts of nitrogen for best growth. In all cases, however, you must add nitrogen by proper fertilization.

The major nutrients needed for quality lawns are nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and iron. All are needed for quality turf, but some are more important than others. Grasses use nitrogen more than any other nutrient. Bermudagrass and zoysiagrass require large amounts of nitrogen during the growing season. Others, including centipedegrass, carpetgrass, and creeping red fescue, require only small amounts of nitrogen for best growth. In all cases, however, you must add nitrogen by proper fertilization.

Some soils in Mississippi indicate a need for phosphorus. However, many soils will have enough phosphorus for most lawn grasses. Soil testing can identify the existing levels of phosphorus in your soil. Don’t add phosphorus unless the soil test shows the need.

Potassium is also called potash. Most soils in Mississippi need it. Potassium is important for proper maturity of turfgrasses. In addition, it helps prevent winter injury and susceptibility to disease.

An important nutrient often overlooked is iron, which is necessary for proper growth and color. In soils with a high pH, iron is often lacking (turf looks yellow-green, similar to lack of nitrogen). Centipedegrass, St. Augustinegrass, and carpetgrass are most affected by iron deficiencies. You can correct an iron deficiency with granular or foliar fertilizer products. Popular materials to add include iron sulfate, chelated iron, and specialty fertilizers with iron. Use each of these according to label directions.

Turfgrasses use various amounts of the different nutrients. Nitrogen is used in the greatest quantity, followed by potassium and phosphorus. Turfgrass research scientists are in general agreement that turfgrasses prefer a 3-1-2 ratio (nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium). This ratio is commonly used in fertilizer recommendations. After the basic soil deficiencies identified by soil testing have been corrected, the 3-1-2 ratio is ideal for most maintenance programs. Often the last application (winter fertilizers) is higher in K than N or at least nearer to a 1-0-1 ratio.

When should you start fertilizing your lawn? This perennial question has been complicated in recent years by data that do not support some long-held beliefs. There are two trains of thought:

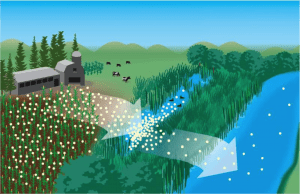

1. “What is best for the turfgrass plant?” Ideally, you should not apply the fertilizer until the turfgrass is actively growing and can readily use the nutrients. Arguments that support this theory include not encouraging weed growth, reducing loss of nutrients to erosion, and not encouraging rapid, succulent growth that is easily damaged by cold.

2. “What is best for the lawn?” Fertilizing before transition (from dormant to full growth) aids in weed control by causing the turfgrass to grow more rapidly and provide a quicker canopy to shade out weed growth. The lawn achieves a darker color and looks better sooner.

There is a problem with early fertilization if the weather gets into a repeated cycle of temperatures warm enough to start top growth, but too short in duration to allow the newly developed leaves to provide carbohydrates to the roots before the leaves are destroyed by cold. All of the carbohydrate stored from last year can be used, and the roots will die from lack of food. This has been quite rare in Mississippi.

Lawn-care providers have several options. Users of conventional, quick-release fertilizers have two options. The old, tried and true method is to wait 2 to 3 weeks after green-up to apply the first fertilizer. The grass plant will come through transition upon stored carbohydrate and residual nutrients from last year.

The second option is to fertilize lightly at the first signs of green-up. This provides additional nutrition for the plants quickly to crowd out weeds. This option makes it possible to use “weed and feed” formulations since the preemerge fertilizers need to be out before germination of the weed seeds. Homeowners can achieve an even distribution of preemerge weed control most easily with these herbicide-carrying fertilizers.

Slow-release nitrogen fertilizers offer the best of both worlds. The fertilizers are available over an extended period of time and will help prevent flushes of rapid growth but will supply additional nutrition for the turfgrass to get off to a rapid start. Slow-release sources, which are temperature dependent (urea formaldehyde, sulfur coated urea), somewhat match fertilizer release with grass growth.

Winterizing Fertilizers

Late-season or “winterizing” fertilizer applications to warm-season turfgrasses in Mississippi is a controversial management practice. The discussion concerns the potential for winterkill, disease promotion, and the effect on total nonstructural carbohydrates (TNC) from late-season nitrogen applications. For high-maintenance turfgrasses (particularly bermudagrass), nitrogen and potassium are nutrients that are required in fairly large amounts during the growing season to provide good growth and quality.

A late-fall application of potassium has been a standard practice because research indicates that potassium promotes winter hardiness and disease resistance in turf. Although some research has indicated an increased vulnerability to winterkill and the promotion of winter diseases from late-season nitrogen applications, similar research studies have shown that late applications of nitrogen prolonged desirable color of Tifgreen bermudagrass into the fall, promoted its recovery in the spring, and had no direct correlation with susceptibility to winterkill.

Research trials conducted at Mississippi State University were designed to simulate a worst-case scenario in which bermudagrass would have an increased likelihood of winterkill resulting from late-season spring turfgrass color ratings with little effect on rhizome TNC levels.

There was no indication that nitrogen fertilization increased bermudagrass winterkill potential. The data indicate that the winterkill phenomenon is probably the result of a combination of factors such as previous cultural and chemical management practices, the environment, or pathogens, and it cannot be attributed solely to late-season fertilization.

Regardless of the time of year, lush turf that is stimulated by excessive nitrogen may be more susceptible to certain diseases. However, properly fertilized turf will have a quicker recovery if it becomes diseased.

A dense, healthy turf is much less likely to have heavy weed populations. Also, people who maintain their lawns with relatively high fertility programs most likely also will maintain good disease and weed management programs.

Although this publication provides general guidelines for fertilization and timings of applications for different turf species in different zones of the state, it does not exclude additional winterizing fertilization to meet specific needs. Winterizing fertilizers are generally formulated to contain lower ratios of nitrogen to potassium, and often the nitrogen sources are not water soluble and are not readily available.

Base your turf fertilization program on soil test analysis, turf use requirements, and grower expectations. Time the application of winterizing fertilizer in the fall, when temperatures begin to moderate and days begin to shorten, but before the turf goes dormant.

Fertilizers: What To Know

Fertilizers come in different strengths. All fertilizers have three numbers on the label. These numbers indicate the kind and strength of fertilizer materials. The first number indicates the percent of nitrogen. The second number indicates the percent of phosphate. The third number indicates the percent of potassium (potash). Many kinds and strengths of fertilizer materials are available.

A mixed fertilizer has nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) combined. Other examples of mixed fertilizers are 24-4-12, 8-8-8, 20-5-10, 24-4-4, 5-10-5, and 13-13-13.

In addition to mixed fertilizers, there are single-source fertilizer materials. These contain only one nutrient. Examples include 21-0-0, a nitrogen fertilizer called ammonium sulfate; 0-20-0, a phosphorus fertilizer called superphosphate; and 0-0-60, a potassium fertilizer called muriate of potash.

All fertilizers are not the same strength. After determining your fertilization program for the year, choose the fertilizer materials compatible with the nutrients recommended for your lawn grass.

Your fertilizer program depends on three things:

1. Which grass you are growing.

2. Which zone you live in.

3. What kind of fertilizer is available.

Begin a fertilization program after you correct liming needs and soil deficiencies. The program shows the nutrient units needed per 1,000 square feet of lawn area for the entire growing season. The rates are based on a 3-1-2 (N-P-K) maintenance ratio.

Since fertilizers are not the same strength, you have to calculate the number of pounds of the fertilizer you plan to use to have the correct recommendation. This is easy to do using this formula:

Pounds of actual nutrients needed divided by percent strength of fertilizer material to be used x 100 = pounds of fertilizer material from the bag that must be applied to 1,000 square feet of lawn area during the entire growing season.

An example: You live in zone 8b and have a bermudagrass lawn. From Table 9, the recommended rate is 6 pounds of actual nitrogen per 1,000 square feet for the growing season. Let’s suppose you wanted to use ammonium sulfate (21 percent strength nitrogen) as the fertilizer material. It is easy to calculate the amount of ammonium nitrate needed to supply a total of 6 pounds of actual nitrogen by using the formula:

(6 ÷ 21) x 100 = 28.57 pounds.

Therefore, nearly 29 pounds of ammonium sulfate (21 percent strength nitrogen) will be needed to supply the 6 pounds of actual nitrogen needed per 1,000 square feet of lawn area for the entire growing season. This 29 pounds should be split into six equal applications as suggested in Table 9. You, therefore, need to apply 5 pounds of ammonium sulfate per 1,000 square feet each of the six times you apply fertilizer to the lawn.

Example: You have a St. Augustinegrass lawn and live in zone 8a. The table recommends you use 2 pounds actual nitrogen per 1,000 square feet per growing season. Assume you want to use a 24-4-12 fertilizer material. Use the formula to determine how many pounds of fertilizer material are needed to supply the 2 pounds of actual nitrogen needed for the entire growing season.

(2 ÷ 24*) x 100 = 8.33 pounds

*Note: Use the largest number of a mixed fertilizer in the formula.

Fertilizer programs for turfgrasses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Type of grass | Where | Recommended amount of actual nutrient for soils testing medium is phosphorus and potassium.* | No. of applications | Optimum time of applications |

Hybrid | Zone 7a | 3 nitrogen 1 phosphate 2 potash | May 15, June 15, Aug 15 | |

Zone 7b | 4 nitrogen 1 phosphate 3 potash | May 1, June 1, Aug. 1, Sept. 1 | ||

Zone 8a | 4 nitrogen 1 phosphate 3 potash | Apr. 15, May 15, June 15, Aug. 15 | ||

Zone 8b | 6 nitrogen 2 phosphate 4 potash | Apr. 1, May 1, June 1 | ||

Seeded | Zone 7a | 3 nitrogen 1 phosphate 2 potash | May 15, June 15, Aug. 1 | |

Zone 7b | 3 nitrogen 1 phosphate 2 potash | May 1, June 1, Aug. 1 | ||

Zone 8a | 3 nitrogen 1 phosphate 2 potash | Apr. 15, May 15, June 15 | ||

Zone 8b | 4 nitrogen 1 phosphate 3 potash | Apr. 1, May 1, June 1, Aug. 1 | ||

Zoysiagrass | Zone 7a | 3 nitrogen 1 phosphate 2 potash | May 15, June 15, Aug. 15 | |

Zone 7b | 4 nitrogen 1 phosphate 3 potash | May 1, June 1, July 1, Aug. 1 | ||

Zone 8a | 4 nitrogen 1 phosphate 3 potash | Apr. 15, May 15, June 15, Aug. 15 | ||

Zone 8b | 6 nitrogen 2 phosphate 4 potash | Apr. 1, May 1, June 1 | ||

St. Augstinegrass | Zone 7a | Not recommended for turf in this zone | ||

Zone 7b | 2 nitrogen 1 phosphate 2 potash | May 1, June 1 | ||

Zone 8a | 2 nitrogen 1 phosphate 2 potash | Apr. 15, Aug 15 | ||

Zone 8b | 3 nitrogen 1 phosphate 2 potash | Apr. 1, June 1, Aug. 15 | ||

Centipedegrass | Zone 7a | Not recommended for turfgrass in this zone | ||

Zone 7b | 1 nitrogen 0 phosphate 1 potash | May 1 | ||

Zone 8a | 1 nitrogen 0 phosphate 1 potash | Apr. 15 | ||

Zone 8b | 2 nitrogen 0 phosphate 2 potash | Apr. 1, Aug. 1 | ||

Carpetgrass | Zone 7a | Not recommended for turfgrass in this zone | ||

Zone 7b | Not recommended for turfgrass in this zone | |||

Zone 8a | 1 nitrogen 0 phosphate 1 potash | Apr. 15 | ||

Zone 8b | 2 nitrogen 0 phosphate 2 potash | Apr. 1, Aug. 1 | ||

Kentucky | Zone 7a | 4 nitrogen 1 phosphate 3 potash | Sept 15, Oct. 15, Mar. 15, | |

Tall fescue grass | Zone 7a | 3 nitrogen 1 phosphate 2 potash | Sept. 15, Mar. 1, Apr. 1 | |

Zone 7b | 2 nitrogen 1 phosphate 2 potash | Sept. 15, Mar. 1 | ||

Creeping red | Zone 7a | 1 nitrogen 0 phosphate 1 potash | September 15 | |