Mehvish Makhdoom, Amna Kanwal, Iqra Ghafoor

Wheat Research Institute, Ayub Agricultural Research Institute, Faisalabad

What causes Karnal Bunt?

Karnal bunt is caused by the fungus Tilletia indica, and is spread by spores (teliospores and sporidia). Teliospores can be carried in soil and on a variety of surfaces, including seed and other plant parts, farm equipment, tools, and even vehicles. Infection occurs after heading when sporidia produced from teliospores at the soil surface are dispersed to the glumes of the wheat spike. The ideal conditions for infection are cool temperatures (15˚-22˚C) and rainfall, overhead irrigation, or high humidity. These conditions must occur during heading and for a few weeks afterward for KB to develop.

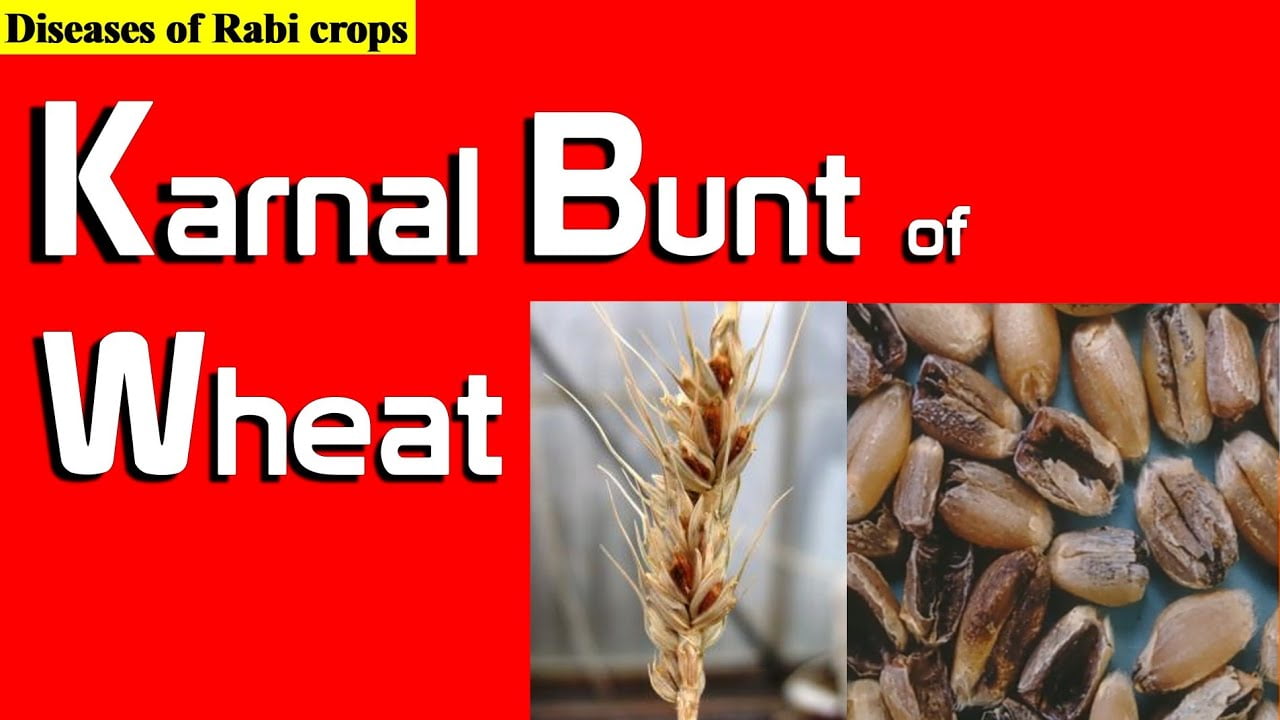

What does Karnal Bunt look like?

Karnal bunt is difficult to identify in the field. Developing wheat kernels are randomly infected and usually only partially converted to the fungus, which is why KB is sometimes called partial bunt. Infection typically occurs in only a few seeds per head, and not all heads on a single plant are infected. Infected grain shows no symptoms until near maturity. Even then the disease is difficult to detect in the field; the grain must be threshed and examined. The diseased portion of kernels is dark (Black) in color and fishy smelling. The kernel usually remains whole, with only a part of the germ end converted into a black powdery spore mass, usually along the kernel groove. Only in extreme cases is the entire kernel converted into spores.

Does Karnal Bunt only affect wheat?

KB affects wheat, durum wheat, and triticale. Rye has been shown to be susceptible with artificial inoculation. Barley and oats are not susceptible. Durum wheats and triticale are less susceptible than hard red and soft white wheats.

Can I consume KB-infected grains?

Yield losses resulting from KB are generally light. The disease does not present a risk to human health, but does reduce flour quality. Generally, wheat containing more than 3 percent bunted kernels is considered unfit for human consumption. Odor and palatability of whole meal and finished products are adversely affected by the chemical trimethylamine produced by the fungus. Pasta products made with flour contaminated with KB spores can have an unacceptable color. At five per cent infection, quality distinctly deteriorates; loss in flour recovery and chemical changes in composition of flour and gluten content cause poor dough strength. Washed and steeped grains in wheat lots with 7-10 per cent infected grains are considered acceptable for consumption.

What can I do to prevent KB?

In the absence of cold and rainy weather, chance of KB is reduced. High rates of nitrogen application and heavy manuring, may also increase the disease incidence. Cultivars sown between November 30 and December 20 are more prone to KB than those sown earlier. The most effective and economical method of controlling the disease is by growing resistance varieties, although the impact of weather during these periods is also recognised.

Will a seed treatment help?

Chemical seed treatments used to control other bunt and smut diseases of wheat are not effective for control of KB because there is insufficient chemical in the plant at heading when infection occurs. Also, the inoculum does not infect the developing seedling as in other bunt diseases nor is it internal to the seed as in smuts.

Since Karnal bunt is soil borne, air borne and seed borne disease. Hot water and solar energy treatments have been applied to KB-infected seeds. However, they have had limited application. For small samples, spores on seed surfaces may be eliminated by disinfesting seeds in a 1.75 percent solution of sodium hypochlorite (i.e., one part of household bleach to two parts of water) plus Tween 20 with agitation for 10 minutes followed by rinsing. Germination of seed treated in this manner is reduced slightly

Soil fumigation: Soil fumigation to control spore germination with some success is reported. In wet soil, methyl bromide reduces spore germination by 98 per cent when buried at depths up to 10 cm. Metam-sodium (Vapam) and formaldehyde were effective only on the soil surface. In dry soil, Vapam reduced germination by 57-99 per cent when spores were buried at depths up to 10 cm.